Anna: Historical Background

Some of the scenes and people depicted in Anna are an imagined composite drawn from historical sources and are a reconstruction of enslaved persons' lives in that place and time: Prince George's County, Maryland, in 1815.

We know little about the life of Ann "Anna" Williams, especially her background before 1815, other than what Jesse Torrey and Ethan Allen Andrews relate about her in their published pieces and what we can glean about her experience from her later freedom suit. Specifically, the following people and events in Anna are based on contemporaneous historical sources:

Marriage

Ann Williams was married, but we do not know her husband's name. No contemporaneous source provides a name for Williams' husband. We refer to him in the film as "Edward." On the complex nature of the broomstick ceremony in the early nineteenth-century, see Tyler D. Parry, "Married in Slavery Time: Jumping the Broom in Atlantic Perspective," The Journal of Southern History 81, no. 2 (May 2015), pp. 273-312.

Slaveholders

There is no mention in the published record of the plantation in Bladensburg where Ann "Anna" Williams was enslaved prior to her sale. When Ethan Allen Andrews spoke with Williams in the 1830s, she referred to her "old master" and being sold to "her husband's master." (See Ethan Allen Andrews, Slavery and the Domestic Slave Trade, p. 129). We have named the slaveholders "Coleridge" and "McCue" respectively.

Violence

It is likely that Anna experienced direct personal violence. All scholarship about this period and enslavement points to routine violence of the sort depicted in Anna. The slap of the "housemistress" enslaver is drawn directly from the ex-slave narrative of James V. Deane from neighboring Charles County, Maryland, who described what happened to his aunt in this way: "The mistress slapped her one day, she struck her back. She was sold and taken south. We never saw or heard of her afterwards." (See Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, Vol. 8, Maryland Narratives, p. 6.)

Skill

There is no mention in the published record of Ann Williams' skill or work before 1815. Numerous plantations were diversifying into weaving and spinning in Prince George's County. We place Ann Williams in this trade. James V. Deane (cited above in the violence section), for example, said that the enslaved in Charles County wore "home-made clothes, the material woven on the looms in the clothes house." He also described the broomstick ceremony.

African Ethnicity

No published source identifies a family history for the character of Ann Williams. We created an imagined reconstruction of her background as Igbo from the Benin region, based on scholarship of the ethnicity of African people brought to the Chesapeake. In particular, we rely on Lorena S. Walsh, "The Chesapeake Slave Trade: Regional Patterns, African Origins, and Some Implications," The William and Mary Quarterly 58, no. 1, New Perspectives on the Transatlantic Slave Trade (Jan. 2001), pp. 139-170, and G. Ugo Nwokeji, "The Atlantic Slave Trade and Population Density: A Historical Demography of the Biafran Hinterland," Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines 34, no. 3 (2000): 616-55.

In November 1815, a woman known only as "Anna" leapt from the third floor window of a tavern in Washington, D.C., after she was sold to Georgia traders and separated from her family.

Abolitionist writers seized on her story, depicting her act as an attempted suicide. For two hundred years, her identity and her ultimate fate remained unknown.1 In 2015, her petition for freedom filed in the Circuit Court for D.C. came to light in the O Say Can You See collaborative research project. Her name was Ann Williams. She suffered a broken back and fractured her arms, but she survived the fall. She and her husband had four more children. Ann won freedom in court for herself and her children in 1832.

News of Anna's alleged suicide attempt spread across the city and eventually reached Jesse Torrey, a physician from Philadelphia who was visiting Washington three weeks later. Shocked by her tale and the slave coffles he was seeing in the nation's new capital, Torrey heard that she had broken her back and both of her arms. Rumors circulated that she had died from the fall.

On December 19th, Torrey visited George Miller's tavern on F Street to inquire about her fate, and his account has been the main source for her depiction in later writings. He found her very much alive, lying on a bed on the floor in the third floor garret, covered with a blood stained white woolen blanket. He learned that her broken arms had not set correctly, that her back had been broken, and that she might not walk again. The slave trader left her behind but took her two girls south to be sold. Torrey also discovered that several others who had been kidnapped and were being held in Miller's Tavern, and he enlisted local lawyer Francis Scott Key to bring a series of habeas corpus cases in the D.C. courts.

At her bedside, seeking some sort of explanation, Torrey asked her why she would have committed "such a frantic act." And she reportedly replied:

They brought me away with two of my children, and would'nt let me see my husband—they did'nt sell my husband, and I did'nt want to go;—I was so confus'd and 'istratcted, that I did'nt know hardly what I was about—but I did'nt want to go, and I jumped out of the window; —but I am sorry now that I did it; —they have carried my children off with 'em to Carolina.

These words were the only verbal record of her story, and even though Torrey published them in his antislavery tract called A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, he did not identify her by name. When published in 1817, Torrey's pamphlet sold poorly and went largely ignored even in antislavery circles in New England. There were efforts to discredit it and vicious rumors swirled that he made up many of the events he recounted, though the documentary evidence recently unearthed proves the veracity of his account.2

In the years that followed, she was known only as "Anna." None of the published accounts of her actions revealed much about her life or social world, instead preferring to use her story to elicit sympathy from whites in the antislavery cause or to promote colonization of blacks out of the United States. Anna's dramatic act prompted a Congressional inquiry in 1816 into kidnapping and the interstate slave trade in Washington, D.C. The Committee chair, Virginia Congressman John Randolph, subpoenaed testimony from Torrey, from the medical doctors who treated Anna, and from his friend Francis Scott Key, a prominent attorney who had helped gather evidence about the kidnappings.3

In the aftermath of the congressional investigation, George Miller's tavern on F Street had become notorious as a place where the inhumanity of the slave trade was laid bare. In fact, Miller accommodated his business to the slave trade so much that the F Street tavern was known in local circles as "the Negro Bastille." Then in April 1819, the tavern caught fire, and some local whites refused on principle to help put out the fire at Miller's Tavern. Instead, they carried water only to neighboring buildings to prevent the fire from spreading. During the fire, some speculated that slaves were chained up in the third floor garret; others recounted the story of the woman who jumped from the window in 1815, saying that she had died of her injuries.4

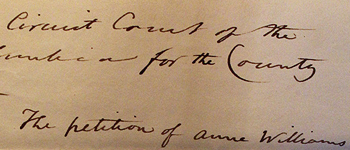

Anna disappeared from the public record after the F Street fire, but thirteen years after her leap from the tavern window, a woman named Ann Williams filed a petition for freedom in the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, claiming that George Miller, Sr., and George Miller, Jr., held her unjustly in slavery.5 Her 1828 petition included her children Ann Maria, Tobias, and John. Her attorney, not coincidentally, was Francis Scott Key, who requested that the court provide a "certificate for their protection" indicating that their freedom petition had been filed and was pending. Clearly, they were concerned that the Millers might attempt to sell Ann Williams and her children now that they sought to claim their freedom. Over the four years from the time she filed her freedom suit to when the case went to trial in the summer of 1832, Ann Williams lived independently and to a large degree as free woman.6

The court repeatedly summoned both George Millers to appear, but for years neither responded. Every six months, Key filed another summons—January 1829, July 1831, February 1832—and the summonses went unanswered. Then on June 27, 1832, Ann discovered that the Millers had taken her twelve-year-old son out of the District, presumably to sell him. Key brought affidavits into the court about the removal, and the court scheduled an immediate jury trial.

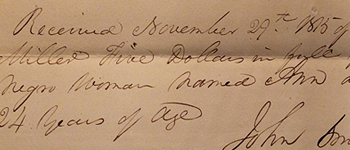

George Miller, Sr., filed a single document in the case: a receipt for his purchase of a 24-year-old woman named Ann on November 29, 1815, for $5. With this bill of sale, Miller could claim he owned not only Ann's once-broken body, but also her yet unborn children. The timing of the purchase and the shockingly low price of sale indicate that Ann Williams was without a doubt the woman who jumped out of Miller's tavern in late November 1815. The court minutes of her trial provide the final proof that Ann Williams was Anna. Among the witnesses who testified on her behalf was William Gardner, one of the men who refused to help put out the fire in 1819 at Miller's F Street tavern. Two doctors were called to testify as well, the same doctors who treated her and the others in tavern: Dr. Benjamin King and Dr. W. Jones.

On July 2, 1832, the jury rendered a verdict for Ann Williams and her children. They were free.7

While the reasons the jury found in favor of Ann Williams were not recorded, the jurors may have determined that she was brought to the District of Columbia in November 1815 to be sold in violation of Maryland law, or that her son in 1832 was about to be taken out of the District to be sold. Under Maryland law, domestic slave traders and slaveholders could not import slaves into Maryland for the purpose of selling them. However, slaveholders with a "bona fide intention of settling" in Maryland could move from other states into Maryland, as long as they registered their enslaved laborers within one year of arrival as a resident. Additionally, the jury may simply have despised Miller and his "Negro Bastille" and could have been predisposed to render a verdict for Ann Williams and her children.8

Three years later, "Anna" returned to the public limelight when she was featured in Ethan Allen Andrews' Slavery and the Domestic Slave-Trade in the United States, a series of letters addressed to the executive committee of the American Union for the Relief and Improvement of the Colored Race. He tracked down Ann in Washington and found her living in freedom, a mother of four children, and able to walk, though with difficulty. Yet, Andrews' sympathy and anti-slavery reformism came with profound limits. He portrayed Anna as a suffering figure, cut off from her family, a symbol for what slavery as a whole did to the enslaved. He barely mentioned Ann's freedom suit. But he did provide details that Torrey did not.

According to Andrews, Ann was born near Bladensburgh, Maryland. When the slaveholder who claimed her fell into debt, he sold her and her two daughters to the man who held her husband on a neighboring plantation. When he too succumbed to his debts, Ann and her children were to be sold to slave trader from Georgia. When this news reached Ann, she begged the slaveholder not to tear her family apart. Seemingly moved by her pleas, he "swore a great oath that they should not be separated." He did not honor his word.

Once the Georgia man saw her condition after her leap from the window, he left her behind with the tavernkeeper, George Miller, taking her daughters away with him to Georgia. But Ann was eventually reunited with her husband who remained enslaved and was able to provide $1.50 a week to support his family. The couple had four more children, though only a son and daugher were yet living in 1835.9

Ann Williams's story was more than a single "frantic act," and her actions were far more calculated and intentional than those who wrote about her were willing to admit. Brought to Washington, D.C., she lost two of her children to the slave trade. Her actions to resist the breakup of her family brought public attention to the moral problem of slavery and to the desperation and terror of the slave trade. George Miller and his tavern became the focal point for the community's resistance to enslavement, and on account of her, some members of the community were willing to let the tavern burn to the ground in 1819. Rather than running away, she fought slavery in one place, accumulating allies, resources, and standing in the community, and eventually, obtaining freedom for herself and her children.

Featured Sources

"But I did not want to go..."

Jesse Torrey's 1817 publication, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery in the United States, included an illustration by Alexander Rider depicting Anna's leap from the garret window.

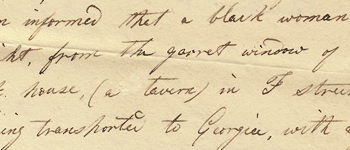

...threw herself from the garret window upon the pavement, broke her arms and legs, and mutilated her body in so shocking a manner that she died shortly afterwards, in the most excruciating agonies...

F Street Fire

Anna became the topic of conversation when George Miller's tavern caught fire in April 1819. Word had circulated erroneously through the neighborhood that she had died of her injuries.

The woman, whom this humane gentleman commiserates so tenderly, is now alive, and in this city, having been restored by the care and attention of my family and myself....

Anna's Fate

Tavernkeeper George Miller portrayed himself as Anna's savior in the aftermath of her fall.

Committee on Traffic in Slaves

Stories like Anna's were described in documents collected by Virginia Congressman John Randolph in his investigation of the slave trade in Washington, D.C.

Receipt from the Purchase of Anna

In November 1815, after Anna jumped from the window, the slave trader who brought her to Washington sold her to George Miller for $5.

Ann Williams' Petition for Freedom

In 1828, Ann Williams filed a petition for freedom against George Miller, Sr, and George Miller, Jr, on behalf of herself and three children.

"Old Anna"

In 1835, Ann was interviewed by scholar Ethan Allen Andrews during his investigation of slavery and the slave-trade in Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

Footnotes

1. For treatments of Anna in the literature, see Robert H. Gudmestad, “Slave Resistance, Coffles, and the Debates over Slavery in the Nation's Capital,” in The Chattel Principle: Internal Slave Trades in the Americas, ed. Walter Johnson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 72-90; Terri Snyder, The Power to Die: Slavery and Suicide in British North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 1-6; Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (New York: Basic Books, 2014), 27-28. See also Candy Carter, “'I Did Not Want to Go': An Enslaved Woman's Leap into the Capital's Conscience” in O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, ed. William G. Thomas III, et al. University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

2. Jesse Torrey, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery in the United States (Philadelphia, 1817), 52; Richard Bell, We Shall Be No More: Suicide and Self Government in the Newly United States (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 217-220. Bell considers Torrey's portrayal of Anna to mark "a turning point" in antislavery and suicide literature. Suicide, he argues, had been the sole act of men of exceptional character, but Torrey's account placed a wife and mother at the center of his indictment of kidnapping and enslavement. By doing so, Bell notes, Torrey suggested to readers that they too would have despaired and attempted suicide. For the most recent assessment of the horrors and violence of slavery, see Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (New York: Basic Books, 2014). For the importance of "soul value" and the perpetuation of the interstate slave trade, see Daina Ramey Berry, The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved from Womb to Grave in the Building of a Nation (New York: Beacon Press, 2017).

3. Francis Scott Key, testimony, April 22, 1816, Select Committee to Inquire into the Existence of an Inhuman and Illegal Traffic in Slaves in the District of Columbia, HR 14A-C.17.4, Committee on the District of Columbia, RG 233, National Archives, Washington, D.C. These documents have been in the NARA vault, inaccessible to scholars for decades. Most scholars cite William T. Laprade, "The Domestic Slave Trade in the District of Columbia," Journal of Negro History 11 (1926): 17-34. For recent references, see Robert M. Gudmestad, A Troublesome Commerce: The Transformation of the Interstate Slave Trade (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004) and "Slave Resistance, Coffles, and the Debates over Slavery in the Nation's Capital," in The Chattel Principle: Internal Slave Trades in the Americas, ed. Walter Johnson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005); and Mary Beth Corrigan, "Imaginary Cruelties? A History of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C.," Washington History 13, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 2001/2002), 4-27, especially 17-18.

4. City of Washington Gazette, April 29, 1819; Wilhelmus B. Bryan, “A Fire in an Old Time F Street Tavern and What It Revealed,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 9 (1906), 198-215.

5. Recent scholarship related to freedom suits and the significance of black legal culture and legal activism has taken off. See especially Kimberly M. Welch, Black Litigants in the Antebellum American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Hendrick Hartog, The Trouble with Minna: A Case of Slavery and Emancipation in the Antebellum North (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Sarah L. Gronningsater, "'On Behalf of His Race and the Lemmon Slaves': Louis Napoleon, Northern Black Legal Culture, and the Politics of Sectional Crisis," Journal of the Civil War Era 7, No. 2 (June 2017): 206-241; Kelly M. Kennington, In the Shadow of Dred Scott: St. Louis Freedom Suits and the Legal Culture of Slavery in Antebellum America (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017); Anne Silverwood Twitty, Before Dred Scott: Slavery and Legal Culture in the American Confluence, 1787-1857 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016); Martha S. Jones, "Leave of Court: African American Claim-Making in the Era of Dred Scott v. Sanford," in Contested Democracy: Freedom, Race, and Power in American History, eds. Manisha Sinha and Penny von Eschen (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 54-74; Lea Vandervelde, "The Dred Scott Case in Context," Journal of Supreme Court History 40, No. 3 (November 2015), 263-281; Honor Sachs, "'Freedom by a Judgment': The Legal History of an Afro-Indian Family," Law and History Review 30, No. 1 (February 2012): 173-203; Jason A. Gilmer, "Suing for Freedom: Interracial Sex, Slave Law, and Racial Identity in the Post Revolutionary and Antebellum South," 82 North Carolina Law Review 535 (2004): 535-619; Lea Vandervelde, Redemption Songs: Suing for Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014); Ariela Gross, Double Character: Slavery and Mastery in the Antebellum Courtroom (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000); Kristen Sword, "Remembering Dinah Nevil: Strategic Deceptions in Eighteenth-Century Antislavery," Journal of American History 97, No. 2 (September 2010): 315-343; Kelia Grinberg, "Freedom Suits and Civil Law in Brazil and the United States," Slavery and Abolition 22, No. 3 (December 2001): 66-82; Brian P. Owensby, "How Juan and Lenour Won Their Freedom: Litigation and Liberty in Seventeenth-Century Mexico," Hispanic American Historical Review 85, No. 1 (February 2005): 39-80; and Edlie L. Wong, Neither Fugitive Nor Free: Atlantic Slavery, Freedom Suits, and the Legal Culture of Travel (New York: New York University Press, 2009). Wong describes the case papers of these suits as "a loose genre of antislavery literature (5). On legal culture and law as a source of cultural production and narratives, see Ariela Gross, "Reflections on Law, Culture, and Slavery," in Slavery and the American South, ed. Winthrop D. Jordan (University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 57-82. Gross notes that slaves were "keenly award of the power of law in their lives" (63). See also Sherwin Keith Bryant, "Slavery and the Context of Ethnogenesis: Africans, Afro-creoles, and the Realities of Bondage in the Kingdom of Quito, 1600-1800," (Ph.D. dissertation, The Ohio State University, 2005), 193; Emilia Viotti da Costa, Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood: The Demerera Slave Rebellion of 1823 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); Maria Elena Diaz, The Virgin, The King, and the Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba, 1670-1780 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000); and John Smolenski, "Hearing Voices: Microhistory, Dialogicity, and the Recovery of Popular Culture on an Eighteenth-Century Plantation," Slavery and Abolition 24, No. 1 (2003): 1-23.

6. Ann Williams, Ann Maria Williams, Tobias Williams, & John Williams v. George Miller & George Miller Jr., in O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, ed. William G. Thomas III, et al., University of Nebraska-Lincoln; 1830 U.S. Census, Ward 2, Washington, District of Columbia, page 80, line 4, Ann Williams, digital image, Ancestry.com, citing NARA microfilm M19, roll 14.

7. “Minute Book Entry,” May 1832, Ann Williams v. George Miller & George Miller Jr., in O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, ed. William G. Thomas III, et al., University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

8. The Slavery Code of the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C., 1862), 3-4.

9. Ethan Allen Andrews, Slavery and the Domestic Slave-Trade in the United States (Boston: Light & Stearns, 1836), 128-133.