Making The Bell Affair

A series of conversations and explorations with the producers, researchers, cast, and crew of the film.

At the beginning of 2020, The Bell Affair team was in full motion. We had major funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to produce a feature-length live action animated film about an enslaved family who sued for their freedom in Washington, D.C. Over three hundred actors responded to our casting call, eager to read for a part. Our script captured the drama and nuance of Black life in ways we hoped would inspire audiences.

Then in early March, the COVID-19 pandemic hit the nation, and our world stopped. The actors were under stay-at-home orders in various states. Our production contractors in Los Angeles and New York were hard hit, unsure how any filming would go forward. It became obvious we could not bring actors from all over the country to our studio in Nebraska for a shoot scheduled in June. Film and media projects shut down around the country. Actors and production companies had nowhere to turn.

At this critical moment, the fate of our film hanging in the balance, Director Kwakiutl Dreher and Senior Producer Michael Burton asked, "Can we produce the film another way?"

We looked for inspiration and found it in places both expected and unexpected. Saturday Night Live at Home debuted on April 11, 2020. And the next morning, Easter Sunday, as Americans turned to virtual church services, the National Cathedral choir and orchestra performed a stunning hymn with 600 participants live-streamed from their individual homes.

We met the next day by Zoom, Monday, April 13, 2020. Stirred by the creative talent at SNL and the National Cathedral, we decided we should try to figure out a way to produce the film in live action animated form without ever having actors be in the same place. Could we create a film entirely in a distributed manner? Would it be as compelling and seamless? Would it meet our expectations? We ran several tests, and after looking at the results, our team was confident we could do this.

So, we are not bringing actors to a studio. We cancelled the June studio time. We shipped all actors their costumes. Our costume designer developed style instructions and conducted virtual fittings with each actor who received a costume at their homes. We provided each actor for each scene a set of technical notes to guide their camera angles for filming themselves. With detailed instructions, actors will film themselves on an iPhone. We've provided equipment as necessary. These changes meant we would need more funds on post-production editing to get this right.

But during the pandemic, from March to August 2020, we have been able to pay our talent and production companies at a time when the industry has struggled.

Then the murders of Ahmaud Aubrey, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd cast the importance of our film in a new light. The summer of 2020 brought a wider American reckoning with the sickening callousness, cruelty, and violence against Black Americans extending back to slavery. The actors in The Bell Affair are well aware of the importance of this history in our current moment.

So the virtual table reads with our actors have taken on fresh urgency and meaning. Every table reading session, each directed by Kwakiutl Dreher, has produced dramatic moments of personal reflection. At one recent table read, the scene featured the discussion of the Bell family about how Daniel Bell should try to negotiate with a white slaveholder for the freedom of his wife Mary and their six children. The scene takes place around the dinner table. After the dramatic reading, Darla Davenport, playing Lucy Bell, Daniel's mother, noted, "This is the kind of scene never shown in film. A Black family making a decision. Together. We need more of this."

– William G. Thomas III

Myeisha Essex (Mary Bell)

What I found to be compelling in our story is that Daniel respects what the women in his life have to say about his decisions, and again, it is something that you don’t necessarily see dramatized onscreen for this particular era. So much is explored and shared of our experiences in this one narrative. Mary Bell is so strong, but it's a kind of strength I cannot fathom. To fight for freedom and your survival and your family unit—and to do that all at once when you have so much coming against you "at every turn"—that's a different kind of strength. At the end to be able to have that scene with her children knowing that she was leaving them in a hell, that's what broke me.

I enjoy the Bells as a family unit, too. I love how Mary and Daniel have raised their children to be emotionally and psychologically free no matter what the world tells them. I like that Mary Bell is a voice in the family unit. There wasn't a scene where Mary does not press Daniel to think about his every strategy and the other areas that needed to be thought out in freedom-making. She impacts his thinking. She asks questions to help Daniel figure out the full plan. At the dinner table, she's not docile and quiet. No. She asks questions. I am so glad to be playing her.

Darla Davenport (Lucy Bell)

I haven't seen the presence of children too much in other feature films and stories. For The Bell Affair team to put children in the story lets me know that the entire Bell family are cut from a cloth of people who dared to speak up and speak out in the midst of it all. As I began to think about the empowerment of children in the story, I thought if more stories about children resisting enslavement had been dramatized, maybe Claudette Colvin's voice would have been respected; maybe Emmett Till's voice would have been respected—these voices of reason that declared, "No, this is not right! I'm going to speak out and stand up in the midst of it." To me, children are closest to purity and to the morality of what is right and wrong. They are not tainted. Even if we look at what's happening now, children, young people, youth, and millennials are at the forefront of demonstrations and declaring what is not right. The children's voices in The Bell Affair inspire me so much in terms of how our children have been at the forefront of movements against injustices in our world.

Tell us a little about your background.

I actually majored in Biomedical art from the Cleveland Institute of Art. While I loved Biomed, I fell in love with the animation industry more and more my senior year. After leaving CIA, I was more of a character designer/illustrator, then moved into technology where I went to Code Bootcamp at Tech Elevator. That is where I fell in love with 3D modeling! I currently attend CG Master Academy for 3D modeling/rigging.

What is most exciting about this project for you?

Since I am newer to 3D modeling, it was exciting working with a team that was so passionate and caring about not only the history of D.C., but the story they were telling and me as a person. It is also exciting to see my work be part of something more than just me and building my portfolio.

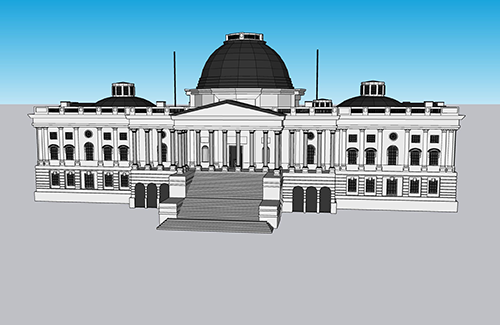

How are you designing the models of buildings from early Washington, D.C.?

All of the models are historic buildings, so a lot of it just comes from research that I do and that I am given. If there are not many visuals, I am usually given excerpts from books that describe the buildings to a T, and then I go from there. Afterward, I might get corrected for minor things like kinds of tiles or sizing, but it's never anything major.

What does this project mean for you in today's world?

With the careful attention to detail and the teams hard work and efforts to make the environment and characters look believable, this project is really exciting to see for a lot of different reasons. Being a black woman myself and having so many roots in Washington, D.C., from my great-grandmother (mother's side) who came here from Georgia in the '40s, and living on 5th street near the Capitol, to my dad taking me downtown every day after school; even to my grandparents (fathers's side) who moved here in the '60s, who recollect often to me how everything was in D.C. during that time and how it has changed. I know people will appreciate all the hard work and time the team has put into this.

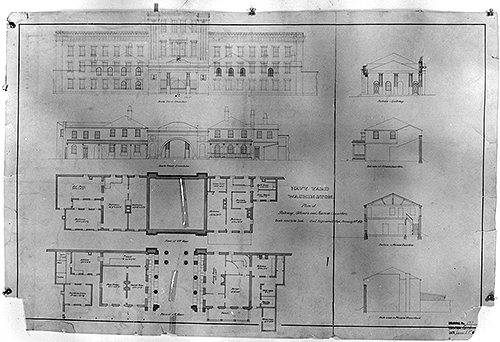

Depicting the world of the Bell family during the early years of Washington, D.C., presented its own unique challenges. The events of the film occur during a decade of change in the national capitol. Between 1836 and 1848, D.C., was a growing city, and many of the buildings we recognize today looked differently in their earlier forms. This was true of the Navy Yard where Daniel Bell and Robert Armstead worked. As a researcher on the film, I was tasked with determining how the Navy Yard would have appeared during their employment, including the steam engine and foundry in the blacksmith shop as well as the iconic Latrobe Gate at the entrance to the yard. In the film, we see blacksmiths at work in the anchor shop, but what would that have looked like in 1848?

It was surprisingly difficult to find descriptions of the workings of the Navy Yard from this time period. Visitors to Washington often described their tour of the Navy Yard, but provided little detail from a visual perspective. Anne Newport Royall (1826) and Jonathan Elliot (1830) were the most useful in their written sketches of the yard, describing the number of forges, furnaces, and steam engines. An historian, Elliot provided a detailed explanation of the complex network of machinery powered by the Navy Yard's lone 14 horsepower steam engine that conveyed power and motion to "two saw gates, . . . two hammers for forging anchors, &c., two large hydraulic bellows, two circular saws, one turning and boring lathe, . . . nine turning lathes, five grind stones, four drill lathes . . . with other machinery, required to facilitate the operations of the several departments in the adjoining buildings."

Government documents published in Congressional records provided further information on the steam engine and its evolution. By 1838, the 14 horsepower engine had been replaced twice and was running at 40 horsepower output.

Royall's description of the Navy Yard was more more literary and evocative than Elliot's. It did not provide specifics about the arrangement or layout of the buildings, but it does give us a window into how the space felt to her at the time—a white, middle class woman in 1824.1 The filmmakers were looking for what the Navy Yard sounded like and an overall vibe of the place as a setting. This is where Royall could help.

"The shops are large and convenient; they are built of brick and covered with copper to secure them from the fire. . . . The number of hands employed vary; at present there are about 200. . . . The whole interior of the yard exhibits one continual thundering of hammers, axes, saws, and bellows, sending forth such a variety of sounds and smells, from the profusion of coal burnt in the furnaces, that it requires the strongest nerves to sustain the annoyance. The workmen are as black as negroes, and the heat of the furnaces at this season of the year, (June,) is insupportable to one not accustomed to it. The whole is one scene of activity, not one is idle."

Because there are no photographs of the Navy Yard during this period, we must rely upon written descriptions and the very few artistic renderings from the time. A Master Plan published by the Naval Facilities Engineering Command in 1979 contained drawn plans showing the evolution of the layout of the Navy Yard from 1799 to 1814 to 1828 to 1866 and beyond. Animators used the information in these plans to reimagine the Navy Yard as it would have looked in 1836 and 1848.

One of the buildings to undergo significant changes was the Latrobe Gate. Originally built as a one-story gatehouse, a second story was added to the guardhouses in 1823. It was eventually renovated further still in 1881 to the three-story Victorian building we see today. Prior to the 1881 renovations, a survey was made of the building which 3D animator Sirrena Infiniti Holmes used to create her model of the gatehouse as it would have appeared during the events depicted in The Bell Affair.

– Kaci Nash

1. For more on Anne Newport Royall, see Cynthia Earman, "An Uncommon Scold," Library of Congress Information Bulletin vol. 59, no. 1 (January 2000).

Sources

Elliot, Jonathan. Historical Sketches of the Ten Miles Square Forming the District of Columbia (1830), 176-182.

Historic American Buildings Survey, Navy Yard, Main Gate, Eighth & M Streets Southeast, Washington, District of Columbia, DC, 1933.

H.R. Doc. No. 21, 25th Cong., 3d Sess. (1838), pp. 355-56.

Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Chesapeake Division, Washington Navy Yard Master Plan (1979).

Royall, Anne Newport. Sketches of History, Life, and Manners in the United States (New Haven, Conn: Barrett Library 1826), 140-143.

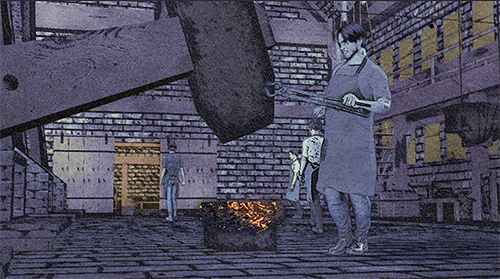

Creating a conversation in the foundry of the Naval Yard where Daniel Bell worked presented a unique cinematic challenge for our team. Timing dialogue and choreographing the physical movement of actors to portray characters performing hard labor required a balance between sound, movement, and dialogue. A coordinated effort was critical to making this a believable scene.

The foundry contained a 14-horsepower steam engine, a large trip-hammer, and a blast furnace roaring in the background. A workforce of both free and enslaved men smelted and poured iron making chains and anchors for America’s Naval fleet. It was a loud environment. Daniel, Joe Thompson, and two other workers hammered super-hot iron blooms while arguing about how to pursue freedom in the courts.

Kwakiutl and I talked about how the different sounds in the foundry would be synced to create rhythm and we experimented with tempos for the men to hammer to. We thought about the ways that chain gangs and Gandy Dancers were depicted in films and how dialogue would be delivered between hammer strikes. We ran several experiments to determine the exact timing for actors to hammer on and how often they would speak. The goal was to create the illusion that Daniel, Joe, and the other workers were out of breath yet still able to carry on a conversation.

Our experiments were carried out virtually using Facetime, a metronome app, and a digital SLR camera. I video video recorded myself hammering a 8-pound sledge hammer while Kwakiutl read the script dialogue. She simultaneously recorded herself.

The metronome was set to a 4/4 timescale since four workers (including Daniel and Joe) were hammering. I hit a wooden block on the first beat for a total of 70 strikes. This allowed us to run through the dialogue entirely and we did this for different tempos. Ultimately we decided that a 70 BPM (beats per minute) was the most natural tempo to maintain conversation during hard physical labor.

I synced Kwakiutl’s voice recording to my video recording and duplicated myself four times to represent each worker. I labeled each character and shared the video with the actors who used it as a guide to memorize their lines and record their footage.

I talked with the actors in the scene during a table read with Kwakiutl explaining the physical motion and the timed choreography involved with swinging a sledge over and over; after all I had been swinging this hammer all afternoon and learned somewhat how to pace myself. Kwakiutl gave performance notes explaining when they should take a breath and when to speak while maintaining a cadence.

Ultimately the 4/4 tempo at 70 BPM was the foundation the entire film soundtrack. Foley sound by Jacob Skoda and the large foundry trip hammer (made by lead animation artist Jordan Scribner) landed on every 3rd bar (12th beat) creating a syncopated bass tone. Composers Jesenia Jackson and Joseph Neidorf used these cues to create the tempo for the entire film score.

– Michael Burton