Historical Background

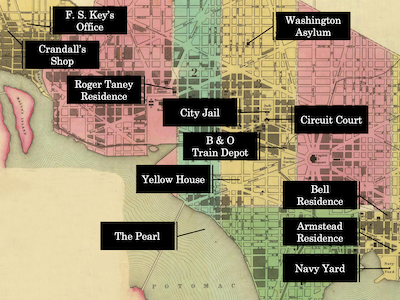

The Bell Affair is an animated documentary, but the story that it portrays is very real, born out of archival documents, the court record, newspaper accounts, and other contemporaneous sources. Below is a guide for each setting of the film and the historical record that informed the decisions made about its portrayal and the events that happened in each of these key places.

In the Bell family home, the strategies of freedom-making spanned four generations. A haven of freedom in a city governed by enslavers, the Bell home was a refuge where the family congregated in times of celebration and freedom-making. Census records and city directories document the close ties the enslaved and free members of the family maintained, even while the institution of slavery tried to keep them apart.

Enslaved in Prince George's County, Maryland, the matriarch of the family, Lucy Bell, and several of her children were sent to work in Washington, D.C., in the early part of the nineteenth century. By the 1830s, Lucy and her daughters, Ann and Caroline, were conducting themselves as free women in the city. Although still enslaved and hired out, Daniel likely lived with Ann and Lucy in their home near the Washington Navy Yard, not far from the Armstead residence where his wife and children were enslaved. For a time before her manumission, Mary resided with her husband, and likely their youngest children.1

Ann Bell appeared to have been literate. She signed her will in 1871 and was known prior to her 1836 freedom petition for conducting herself as a free woman, purchasing real estate, building a house, and hiring servants. Savvy, knowledgeable, and aware of the pathways to freedom through the law, Ann eventually sued for her freedom. She likely knew that Robert Armstead was a signatory for the 1828 memorial that criticized, in particular, slavery's separation of families and the enslavement of people who were entitled to their freedom.2

1. Lucy Bell in 1820 Federal Census, Washington Ward 5, Washington, District of Columbia, Pages 88-90, M33, Roll 5, digital image, Ancestry.com; Daniel Bell and Ann Bell in 1850 United States Federal Census, Washington Ward 5, Washington, District of Columbia, dwelling 236, families 279, 280, NARA Roll M432_57, Page 108A, Image 222, digital image, Ancestry.com; Ann Bell v. Gerard T. Greenfield, Jury Instructions, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0104.007; Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, Petitioner's Bills of Exceptions, December 6, 1847, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0172.005. See Mary Beth Corrigan, "A Social Union of Heart and Effort: The African-American Family in the District of Columbia on the Eve of Emancipation," Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Maryland, 1996.

2. Last Will and Testament of Ann Bell, 19 Sept. 1871, Probate Records (District of Columbia), 1801-1930, District of Columbia Register of Wills, Washington, D.C.; Ann Bell, Daniel Bell, and David Bell v. Gerard T. Greenfield, https://earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.caseid.0104; District Of Columbia, Memorial of inhabitants of the District of Columbia, praying for the gradual abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia (Washington: Printed by Gales & Seaton, 1828), https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.supp.0004.001.

For more information on the Bell family, see Kaci Nash, "Emancipating the Bell Family: An Inquiry into the Strategies of Freedom-Making" in O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, edited by William G. Thomas III, et al. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2018) https://earlywashingtondc.org/stories/emancipating_bells. See also Tamika Y. Nunley, At the Threshold of Liberty: Women, Slavery, and Shifting Identities in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), for more information on Black women in nineteenth-century Washington, D.C., and Jessica Marie Johnson, Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

During the first week of August 1835, three interrelated bouts of unrest occurred almost simultaneously in the streets of Washington, D.C., each one fueling the other, and highlighting the racial tensions in the nation's capital.

Rioting began with a strike in the Navy Yard. For years, the labor competition between free and unfree labor had stirred up conflict based on the racial and social hierarchies in the city, the result of urban slavery and wage labor capitalism. The use of slave labor at the Navy Yard and other public works drew condemnation from residents of the city. "The employ of slaves," accused one, "prevents white men from accepting work amongst them[,] as the whites feel it to be a degradation... many came to the city of Washington with their wives, sons, and daughters, but they returned disgusted, as they would not associate with negro slaves."1

A minor incident at the Navy Yard provoked the strike. After a thief stole a few items from one of the shops during lunch, the Commandant of the Navy Yard imposed restrictions on the meals of the mechanics and laborers. In response, the white mechanics initiated a strike on July 31, 1835. About a week later, a young enslaved man named Arthur Bowen was arrested on suspicion of attempted murder. Rumors swirled that he had gotten drunk one night, and with axe in hand, stumbled into the bedroom of his enslaver, a prominent widow in the city. Newspapers called the incident "one of the effects of the fanatical spirit of the day, and one of the immediate fruits of the incendiary publications with which this city and the whole slave-holding portion of the country have been lately inundated."2 Within days of Bowen's arrest, an itinerant professor of botany, Reuben Crandall, was apprehended for circulating "incendiary" abolitionist literature.

Crandall and Bowen became fresh targets for the strikers' aggrieved sense of injustice and anger. Both represented what white workers feared most: the threat of further competition from emancipated Blacks who might seek out urban centers like Washington, D.C. The strike at the Navy Yard gradually turned into a mob. After rioting at the city jail where Crandall and Bowen were being held failed to produce any results, the white mechanics turned their ire against Beverly Snow, a successful free Black man who was rumored to have said something disparaging against one of the mechanic's wives. The rioters destroyed Snow's restaurant, the Epicurean Eating House, and invaded his home. After a few more acts of destruction aimed at Black Washingtonians, the rioting dissipated.3

1. "On the City Slave Tax," Daily National Intelligencer, March 26, 1816.

2. Daily National Intelligencer, August 7, 1835.

3. Patrick Hoehne, "Rereading the Riot Acts: Race, Labor, and the Washington, D.C. Snow Riot of 1835," Riot Acts, riotacts.org/stories/snowriot.html.

Roger B. Taney and Francis Scott Key began their law careers together in the early 1800s. Professionally and politically connected, Taney also married Key's sister Anne. Both Taney and Key harbored seemingly contradictory views on slavery.1 Each manumitted most of the people they personally held in bondage. Each publicly opposed the transatlantic slave trade. Each was a major supporter of colonization and active in the Maryland chapter of the American Colonization Society. As a member of the Maryland State Senate, Taney voted in support of restrictions on the expansion of slavery. And in 1819, he defended Jacob Gruber, a white minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church who was arrested for an anti-slavery sermon at a camp meeting in Maryland, upon charges of endeavoring to "stir up, provoke, instigate, and incite, divers negro slaves." Taney's opening statement at trial in defense of Rev. Gruber was profoundly anti-slavery:

There is no law that forbids us to speak of slavery as we think of it. Any man has a right to publish his opinions on that subject whenever he pleases. It is a subject of national concern, and may at all times be freely discussed. . . . A hard necessity, indeed, compels us to endure the evil of slavery for a time. It was imposed upon us by another nation, while we were yet in a state of colonial vassalage. It cannot be easily, or suddenly removed. Yet while it continues, it is a blot on our national character, and every real lover of freedom, confidently hopes that it will be effectually, though it must be gradually, wiped away; and earnestly looks for the means, by which this necessary object may be best attained. And until it shall be accomplished: until the time shall come when we can point without a blush, to the language held in the declaration of independence, every friend of humanity will seek to lighten the galling chain of slavery, and better, to the utmost of his power, the wretched condition of the slave. Such was Mr. Gruber's object in that part of his sermon, of which I am now speaking. Those who have complained of him, and reproached him, will not find it easy to answer him: unless complaints, reproaches and persecution shall be considered an answer.2

The jury returned a verdict of not guilty. Taney's lawyering for Gruber was just that, lawyering. Attorneys like Taney and Key were expected to be zealous advocates for their clients, whatever their position in society.

A few years earlier, Taney's wife, Anne Key Taney, provided testimony to prove the freedom of Robert Patterson, an African American man who had been an apprentice of her father. "The said Robert," Anne affirmed, "was Freeborn - that he was one of the Toogood family adjudged to be free - being the son of Debby Toogood whom this Deponent has frequently seen & understood to have obtained her freedom by petition to some court of this state."3

By 1835, Taney's political views on slavery and Black freedom were more clear. As Attorney General in the Jackson administration, he wrote that Blacks were not persons under the meaning of the Constitution and had no rights. The opinion was a precursor to his later infamous Dred Scott decision. In the summer of 1835, Chief Justice John Marshall died, and Taney nursed his ambition to be appointed to lead the Supreme Court.

As the U.S. District Attorney for Washington, D.C., Francis Scott Key elevated Taney's nomination to the Court and sought to prosecute abolitionists like Reuben Crandall. Despite frequently appearing as an attorney for enslaved people filing freedom suits, his views on Black freedom similarly hardened. Neither Key nor Taney could envision Black freedom in the United States. Both supported colonization to remove free Blacks.

During his prosecution of Reuben Crandall, Key betrayed plainly racist views. Defending his own past comments supporting the Colonization society, Key revealed his disgust for Crandall's abolitionism:

The "great moral and political evil" of which I speak, is supposed to be slavery—but is it not plainly the whole coloured race? But if I did say this of slavery, as I am quite willing to say it, here and on all fit occasions, do I not also in the same breath speak of emancipation as a far greater evil? . . .

Slavery is an evil—therefore to be immediately eradicated; slavery is a sin—therefore to be immediately abandoned. Yet there are evils which admit only of gradual remedies—evils, which cannot at certain times and under certain circumstances be removed, without being followed by still greater evils. . . .

That slavery is an evil, he believed, was felt and acknowledged by a very large proportion of the people of the slave States: but they felt and knew that it was a necessary evil, not to be removed (except gradually, and on the condition of colonization,) without being followed by far greater evils. His own experience and observation (he said) had greatly changed his opinions and feelings on this subject. In the course of his professional life he had (as their Honors on the bench well knew) been the common advocate of the petitioners for freedom in our courts. He had tried no causes with more zeal and earnestness. He had considered every such cause as one on which all the worldly weal or woe of a fellow creature depended, and never was his success in any contests so exulting as when, on these occasions, he had stood forth as the advocate of the oppressed, "The poor his client, and Heaven's smile his fee." But an experience of thirty five years had abated much of his ardour——for he had seen that much the greatest number of those in whose emancipation he had been instrumental, had been far from finding in the result the happiness he had expected. Instead of the blessings that he had believed were thus to be conferred upon them, the subsequent history of those persons had showed him that in most cases (there were a few consoling exceptions) the change of their condition had produced for them nothing but evil.4

1. For more about Taney and Key and their views on slavery, see William G. Thomas III, A Question of Freedom: The Families Who Challenged Slavery from the Nation's Founding to the Civil War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 146-147, 205-206, 230, 243-244, 261-262.

2. Timothy S. Huebner, "Roger B. Taney and the Slavery Issue: Looking Beyond—and Before—Dred Scott," The Journal of American History 97, no. 1 (2010): 17-38, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40662816; David Martin, Trial of the Rev. Jacob Gruber, Minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church, at the March Term, in the Frederick County Court, for a Misdemeanor (Fredericktown, MD: David Martin, 1819), https://www.loc.gov/item/20012686/.

3. "Sworn statement of Anne Taney concerning the status of Robert (Toogood) Patterson," Box 1, Papers of Roger B. Taney, MSS 87-3, Special Collections, University of Virginia Law Library, https://archives.law.virginia.edu/records/mss/87-3/digital/4680.

4. Francis Scott Key, A Part of a Speech Pronounced by Francis S. Key, Esq. on the Trial of Reuben Crandall, M.D. (Washington: 1836), YA Pamphlet Collection (Library of Congress), 9-12, https://www.loc.gov/item/31010419/.

Reuben Crandall's botany shop was likely located on High Street in Georgetown. According to one witness in his trial, "it was a private office, and was kept locked. . . . There was no name over the door—nothing to indicate a doctor's shop—nothing ordinarily in a doctor's shop, except books. There was nothing in the windows or in the shop for public sale." Another said, "He used newspapers, or something like them, for enclosing his plants first, and afterwards wrapped them in white paper."1

When the justices of the peace entered Crandall's shop, they questioned him about abolitionist leanings. And later, during the hack ride to the D.C. Jail, Jeffers and Robertson pushed him further. According to courtroom testimony:

Witness remembers that there was a conversation in the hack, as they were coming from Georgetown to the jail, in which the following question was asked Dr. Crandall:—"Don't you think it would be rather dangerous, at the present time, to set all the negroes free?" Don't recollect the precise words of the reply, but he inferred from it——

The Court interposed. We don't want your inferences, Mr. Robertson; give us the facts, if you please.

Well, if it please the Court, continued Mr. Robertson, my impression was, at the time, that Dr. Crandall's reply amounted to this—that he was for abolition, without regard to consequences. Mr. Jeffers asked the Doctor if he did not think that abolition would produce amalgamation and also endanger the security of the whites. The doctor did not object to these consequences. He thought the negroes ought to be as free as we were. . . .

In the course of the conversation in the hack, Crandall said he did not intend to deny his principles. Witness asked him if colonization would not be better than abolition. He replied: No; he was in favor of immediate emancipation.2

1. Jefferson Morley, Snow-Storm in August: Washington City, Francis Scott Key and the Forgotten Race Riot of 1835 (New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2012); The Trial of Reuben Crandall, M.D. (New York: H. R. Piercy, 1836), https://www.loc.gov/item/18013204/.

2. The Trial of Reuben Crandall, M.D. (Washington: 1836), https://www.loc.gov/item/18013203/

In 1835, the Washington Asylum referred to the almshouse located on West 7th street between M and N. It was also called the Infirmary. Travel writer Anne Newport Royall had little good to say about the institution when she visited it in 1824.

This wretched establishment only exists to disgrace Washington. . . . I asked one of the unfortunate women whose business it was to attend to these sufferers, what made the rooms smell so ill; but she was too simple to understand me. The intendant and his wife are Irish; he appeared to me to be wholly unfit for the place, and his wife a perfect she dragon. It is much to be lamented, that in such cases care is not taken to select persons of humanity, who are capable of administering comfort and consolation to affliction. The house is large and beautiful, and in the finest situation in the city, but death would be mercy compared to the situation of the unfortunate inmates.1

Robert Armstead's presence at the almshouse became a contentious issue during the proceedings of Mary Bell's freedom suit. Armstead's widow Susan argued that the Bells used the Washington Asylum as the setting for signing of the manumission deed because it was "away from and out of the presence of his friends and family without their knowledge." Susan Armstead called witnesses from the almshouse to testify to her late husband's mental incompetence when he signed the manumission deed.

The deed was signed in the presences of George Naylor, a justice of the peace for Washington County, and Richard Butt, the intendent of the Washington Asylum at the time. The circumstances of the signing as well as the events leading up to it, as depicted in the film, are detailed in the court record.2

Armstead appeared to use the Asylum for his medical care. A Dr. McWilliams—likely Alexander McWilliams, a well-respected medical practitioner in the city—attested that he attended to Armstead three or four times a week at the almshouse for his chronic rheumatism. "I had no reason to believe he was insane or a man so weak intellect as to be incapable of understanding the effect and operation of a deed of manumission," McWilliams stated, "although I thought him to be a weak man in intellect." In the court records, Mary Bell described Armstead's ailments as a "great physical debility, that he was afflicted with chronic Rheumatism; and . . . was afflicted with a diseased state of the bowels."3

1. Judah Delano, The Washington Directory (Washington: William Duncan, Twelfth Street West, 1822); Anne Newport Royall, Sketches of History, Life, and Manners in the United States (New Haven, Conn: Barrett Library 1826), 143.

2. Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, Petitioner's Bill of Exceptions, December 6, 1847, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0172.003; Affidavits from Almshouse, March 31, 1837, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0172.002; Deed of Manumission, September 14, 1835, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0243.007; Petitioner's Bills of Exceptions, December 6, 1847, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0172.005.

3. "Death," Daily National Intelligencer, April 2, 1850; Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, McWilliams' Answers to Interrogatories, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0172.009; Petitioner's Bills of Exceptions, December 6, 1847, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0172.005.

Daniel Bell worked in the blacksmith's shop of the Washington Navy Yard, one of many free and enslaved Black workers there. Several men in the Navy Yard sued for their freedom. They would have shared knowledge about lawyers, the courts, and the legal process of suing for freedom. Blacksmith Joe Thompson petitioned for his freedom and that of his wife and daughter in 1815, because his manumission had been disregarded by his slaveholder's heirs after his death. Francis Scott Key and Augustus Taney, brother of Roger Taney, were the Thompsons' attorneys. Joe, Nelly, and Sarah Anne Thompson were freed by the court in 1817.

Another worker at the Navy Yard, Michael Shiner orchestrated a freedom suit in 1833 for his wife Phillis in Alexandria and their three daughters, who were being held in the Alexandria jail. Shiner recorded the incident in his diary:

the 5 day of June 1833 on wensday my Wife and Childdren philis Shiner wher sold to couple of gentelman Mr Franklin and mr John armfield and wher caried down to alexandria on the Six day of June 1833 on Thursday the 7 day of June 1833 on friday i went to alexandria 3 times in one day over the long Bridge and i wher in great distress But never the less with the assistance of god i got My Wife and Childdren Clear

Just as Daniel Bell did, Shiner filed his own freedom suit in 1836. By 1840, the Shiners were free.1

At the time, the Navy Yard was at the height of technological sophistication. In 1830, historian Jonathan Elliot provided a detailed explanation of the complex network of machinery powered by the Navy Yard's lone 14 horsepower steam engine that conveyed power and motion to "two saw gates, . . . two hammers for forging anchors, &c., two large hydraulic bellows, two circular saws, one turning and boring lathe, . . . nine turning lathes, five grind stones, four drill lathes . . . with other machinery, required to facilitate the operations of the several departments in the adjoining buildings." Less than ten years later, the 14 horsepower engine had been replaced twice over and was running at 40 horsepower output.2

Another account of the Navy Yard during the early years of the District described the workshops as "large and convenient."

They are built of brick and covered with copper to secure them from the fire. . . . The number of hands employed vary; at present there are about 200. . . . The whole interior of the yard exhibits one continual thundering of hammers, axes, saws, and bellows, sending forth such a variety of sounds and smells, from the profusion of coal burnt in the furnaces, that it requires the strongest nerves to sustain the annoyance. The workmen are as black as negroes, and the heat of the furnaces at this season of the year, (June,) is insupportable to one not accustomed to it. The whole is one scene of activity, not one is idle.3

1. Michael Shiner, The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, ed. John G. Sharp, Naval History and Heritage Command, Introduction, 52, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html.

2. Jonathan Elliot, Historical Sketches of the Ten Miles Square Forming the District of Columbia (Washington: J. Elliot, Jr., 1830), 176-182; H.R. Doc. No. 21, 25th Cong., 3d Sess. (1838), pp. 355-56.

3. Anne Newport Royall, Sketches of History, Life, and Manners in the United States (New Haven, Conn: Barrett Library 1826), 140-143.

The details of Daniel Bell's seizure from the shop floor at the Navy Yard were described in a New York Daily Globe article that circulated in numerous New England newspapers during the fall of 1848. "The master of Bell," the article stated, "in a rage, because the owner of his wife had set her free by deed, sold him to the speculators. They came into the shop while at his work—without warning, he was knocked flat on the floor by them, ironed and carried to the trader's pen, then kept in Seventh street on the Avenue." At the time, there were several slave pens located near that address, however, it is very likely that Bell was taken to the notorious jail held by slave trader William H. Williams. Four years later, Williams would purchase Daniel's brother-in-law, James Ash, from the Greenfield family that enslaved them both.1

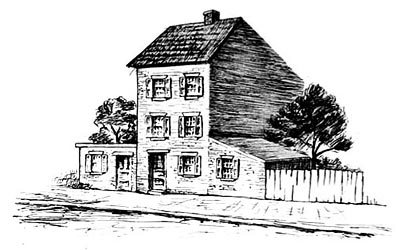

Known as the Yellow House, Williams' slave jail was the location of Solomon Northup's imprisonment after he had been kidnapped in 1841. Northup provided a detailed description of the place in his 1853 memoir, 12 Years A Slave:

The light admitted through the open door enabled me to observe the room in which I was confined. It was about twelve feet square—the walls of solid masonry. The floor was of heavy plank. There was one small window, crossed with great iron bars, with an outside shutter, securely fastened.

An iron-bound door led into an adjoining cell, or vault, wholly destitute of windows, or any means of admitting light. The furniture of the room in which I was, consisted of the wooden bench on which I sat, an old-fashioned, dirty box stove, and besides these, in either cell, there was neither bed, nor blanket, nor any other thing whatever. The door . . . led through a small passage, up a flight of steps into a yard, surrounded by a brick wall ten or twelve feet high, immediately in rear of a building of the same width as itself. The yard extended rearward from the house about thirty feet. In one part of the wall there was a strongly ironed door, opening into a narrow, covered passage, leading along one side of the house into the street. The doom of the colored man, upon whom the door leading out of that narrow passage closed, was sealed. . . . It was like a farmer's barnyard in most respects, save it was so constructed that the outside world could never see the human cattle that were herded there.

The building to which the yard was attached, was two stories high, fronting on one of the public streets of Washington. Its outside presented only the appearance of a quiet private residence. A stranger looking at it, would never have dreamed of its execrable uses. Strange as it may seem, within plain sight of this same house, looking down from its commanding height upon it, was the Capitol. The voices of patriotic representatives boasting of freedom and equality, and the rattling of the poor slave's chains, almost commingled. A slave pen within the very shadow of the Capitol!2

1. "Beauties of the Slave System," The North Star, October 13, 1848; James Ash v. William H. Williams, https://earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.caseid.0149.

2. Solomon Northup, 12 Years A Slave (Buffalo: Derby, Orton and Mulligan, 1853), 41-43.

For further information on William H. Williams and the Yellow House, see Jeff Forret, Williams' Gang: A Notorious Slave Trader and His Cargo of Black Convicts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

When Robert Armstead died in September 1835, the family was in dire straits financially. Armstead's poor health kept him from working in the small shop he had established in his home after he became incapable of continuing his work at the Navy Yard. The inventory of his estate was taken four years after his death and contained only a very few household furnishings. Of the $1,299.25 appraised, only $74.25 was not in human property. The appraiser priced the six Bell children at $1,225. Mary Bell was listed as "not produced," alongside several pieces of furniture.1

Susan Armstead's solution to the problem of the manumission deed seemed to be to ignore it entirely. According to court documents filed by Mary Bell in September 1844, Armstead and two men had begun "pursuing" Mary and her daughter Eleanora, who had been born after the manumission deed, "with the avowed intention of selling them" out of Washington, D.C. Armstead eventually seized Eleanora from the Bells and made further plans to send Harriet out of the District. Mary's petition for freedom went to trial in 1847. The jury found in favor of Susan Armstead. When Mary's attorney filed a motion for a new trial, the Bell family had already begun seeking other avenues of obtaining their freedom.2

1. Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, Petitioner's Bills of Exceptions, December 6, 1847, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0172.005; Estate of Robert Armstead, RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case File 1832, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

2. Mary Bell v. Susan Armstead, James C. Deneale, & David Little in Loren Schweninger, ed., Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks: Petitions to Southern Legislatures and County Courts, 1775-1867 [microfilm], Series II, Part B, Roll 15, #20484405; "Petition," July 1, 1846, Harriet Bell v. Susan Armistead, in Schweninger et al., Race, Slavery and Free Blacks, Series II, Part B, Roll 15, #20484601.

The lengths to which Susan Armstead went to keep her enslaved property are not unusual to slaveholding white women. See Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

At the time of the trial of Reuben Crandall and the Bell family freedom suits, the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia was being held in a courtroom on the east side of the City Hall building at Judiciary Square.1

The details of Daniel Bell's negotiation for his freedom were described in an New York Daily Globe article that circulated in numerous New England newspapers during the fall of 1848. "Beauties of the Slave System" discussed the legal case against Drayton and Sayres and provided vignettes of the Bell and Edmondson families. Of Daniel, it stated:

Bell had friends, who pitied him, and his distressed wife and children. They induced a Colonel somebody, of the marine corps, to purchase him, and gave him a chance to work out his freedom. Bell was to pay a thousand dollars for himself. He had actually paid the amount, or near it, when his owner, the Colonel, was ordered to Florida, where he died. It was then found that he had mortgaged Bell to his sister-in-law, for a thousand dollars, before leaving home. She demanded of Bell the whole sum, but he sank into despair, and told her he must die a slave after all, for he never could raise that amount. Through the intervention of a trusty friend, Thomas Blagden, who had from the first endorsed Bell's notes for him, he got the price finally reduced to five or six hundred dollars. The sum of the matter is, Bell has the receipts to show that he has actually paid $1,630 for himself!2

The identity of the Marine colonel was never revealed; however, research suggests that it may have been Charles R. Broom. Broom was a neighbor of Robert Armstead, and the 1840 census indicated that an enslaved man between the age of 24 and 35 resided in the household. The Daily Globe article stated that the colonel was in Florida when he died. Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Broom was the paymaster of a regiment of Marines stationed at Fort Brooke, Florida, although he was detached to Washington, D.C., when he died in November 1840.3

The Bell family had varying degrees of success through the law. Daniel's sister, Ann, and her two children, won their freedom suit in April 1840. The Bells' brother-in-law, James Ash, won his freedom in January 1843 in a decision affirmed by the Supreme Court. In all, there were seven petitions filed in the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia by members of the Bell family.4

- Daniel Bell v. John Stephenson (1835)

- Ann Bell, Daniel Bell, & David Bell v. Gerard T. Greenfield (1836)

- James Ash v. William H. Williams (1839)

- Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead (1844)

- Harriet Bell v. Susan Armistead (1846)

- Eleanora Bell v. Susan Armistead (1849)

- Caroline Butler v. Fielder Magruder (1850)

While the Bell family were navigating their own path to freedom, abolitionists were being prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law by the District Attorney, Francis Scott Key. Reuben Crandall's trial was a sensational one by the standards of 1836 Washington. Up to that point, there had never been a trial for libelous sedition, and the nation's capital provided a dramatic stage for events to unfold. Key's prosecution resurrected common law ideas about libelous sedition from the 1790s and flew in the face of the 1st Amendment. Hundreds of spectators thronged to the galleries to watch the spectacle. Crandall, jailed for months, contracted tuberculosis and appeared visibly weakened at trial.5

Key charged Crandall with numerous indictments, among them:

The third count charged the defendant with publishing twelve other libels, in which are represented and exhibited "several disgusting prints and pictures of white men in the act of inflicting, with whips, cruel and inhuman beatings and stripes upon young and helpless and unresisting black children; and inflicting with other instruments, cruel and inhuman violence upon slaves, and in a manner not fit and proper to be seen and represented; calculated and intended to excite the good people of the United States in said county to violence against the holder of slaves in said county as aforesaid, and calculated and intended to excite the said slaves in said county, to violence and rebellion against their said masters in said county; in contempt of the laws, to the disturbance of the public peace, to the evil example of all others, and against the peace and government of the United States."6

Crandall's attorney, Richard S. Coxe, objected to Key's central premise that a person could be prosecuted for possessing, or even publishing, abolitionist views:

It is, gentlemen, preposterous—it is monstrous. It has no foundation in any principle of law—it can find no support in any dictate of reason. It is a reproach to our community—it is a slander upon our institutions, that an intelligent and highly accomplished individual, should, under such circumstances and upon such grounds, have suffered what has already been inflicted upon him. True, he is a stranger. But among the brightest and the most attractive characteristics of the south, has hitherto been her generous hospitality. Thousands of southern men have partaken of the liberal hospitality of the north. If this be the mode in which it is to be reciprocated—if stranger and enemy are to be with us convertible terms—if to come from the north be evidence of guilt, or even cause of suspicion, all the kindness which many of us have witnessed, must be at an end, and upon our own heads must rest the consequences.7

Twelve years later, Francis Scott Key's son, Philip Barton Key, held his father's position as U.S. Attorney, and prosecuted Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres, the men held responsible for the attempt at freedom by the fugitives on the Pearl. While the Bells pushed for their freedom in public courtrooms and in secret, their allies and advocates for the abolition of slavery were punished for their own efforts and beliefs.

1. F. Regis Noel and Margaret Brent Downing, The Court-House of the District of Columbia (Washington: Judd & Detweiler, Inc., 1919), 93-94.

2. "Beauties of the Slave System," The North Star, October 13, 1848.

3. Kaci Nash, "Emancipating the Bell Family: An Inquiry into the Strategies of Freedom-Making," O Say Can You See, https://earlywashingtondc.org/stories/emancipating_bells; Capt. Broom in 1830 United States Federal Census, Washington Ward 6, Washington, District of Columbia, NARA Roll M19_14, Page 33, digital image, Ancestry.com; Charles R. Broom in 1840 United States Federal Census, Washington, District of Columbia, NARA Roll 35, Page 106, digital image, Ancestry.com; Florida, Fort Brooke, 1824 Jan - 1840 Dec, Returns From U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M617, 1,550 rolls), Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780s-1917, Record Group 94, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Charles R. Broom obituary, The Madisonian, November 17, 1840.

4. For more information on the Bell family's freedom suits, see Kaci Nash, "Emancipating the Bell Family: An Inquiry into the Strategies of Freedom-Making," O Say Can You See, https://earlywashingtondc.org/stories/emancipating_bells.

5. Jefferson Morley, Snow-Storm in August: Washington City, Francis Scott Key and the Forgotten Race Riot of 1835 (New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2012).

6. The Trial of Reuben Crandall, M.D. (Washington: 1836), 8, https://www.loc.gov/item/18013203/.

7. The Trial of Reuben Crandall, M.D. (New York: H. R. Piercy, 1836), 57, https://www.loc.gov/item/18013204/.

What began as the Bell family's attempt to escape enslavement at the hands of Susan Armstead eventually turned to become one of the largest escape attempts in the history of slavery in the United States. After Mary Bell's freedom suit failed in the courts, Daniel Bell, with the help of abolitionist intermediaries, facilitated the hiring of a captain to charter a schooner to convey his wife, children, and two grandchildren out of the District to Frenchtown, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore. Friends were to meet them there and convey them to Philadelphia and out of slavery's reach. Word spread through the free and enslaved community of D.C., and by the time the Pearl pushed off from the wharf, the number of enslaved people seeking their freedom aboard the ship had swelled from the 11 members of the Bell family to at least 77 people. The escape plan gained notice, and slaveholders dispatched an armed steamer to intercept the Pearl. Becalmed in the Potomac River near the open water of the Chesapeake Bay, the posse captured the Pearl, boarded the vessel, and steamed back to Washington, D.C., with the Pearl in tow.

The ship's captains, Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres, led the manacled procession of men, women, and children through the streets of Washington to the City Jail. An unruly crowd followed, their ire directed at both the freedom seekers and the two white men who had aided in their attempted escape. Eventually, Drayton and Sayres had to be conveyed the rest of the way by hack in order to keep the crowd from laying hands on them.

After two subsequent trials, Drayton and Sayres were sentenced to fines and costs for the transportation of runaway enslaved people. Until the enormous sum was paid, both men were to remain in the city jail—a veritable life sentence. They were eventually pardoned by President Millard Fillmore.1

The exact location of the wharf from which the Pearl departed is unknown. Area newspapers identified the wharf variously as "the steamboat wharf, below the Long Bridge"; "the wharf at the foot of Seventh street"; and "not far from Greenleaf's point." In his memoir, Daniel Drayton described the docking location of the Pearl as "a rather lonely place, called White-house Wharf, from a whitish-colored building which stood upon it. The high bank of the river, under which a road passed, afforded a cover to the wharf, and there were only a few scattered buildings in the vicinity. Towards the town there stretched a wide extent of open fields."2

1. Kaci Nash, "Emancipating the Bell Family: An Inquiry into the Strategies of Freedom-Making," O Say Can You See, https://earlywashingtondc.org/stories/emancipating_bells; Stanley Harrold, Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865 (Baton Rouge; LSU Press, 2002), 116-145; Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad (New York: William Morrow, 2007); Josephine F. Pacheco, The Pearl: A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Daniel Drayton, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton (Boston: Bela Marsh, 1853), 101-102 .

2. Daily Union, April 19, 1848; Daily National Intelligencer, April 19, 1848; Alexandria Gazette, April 19, 1848; Drayton, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton, 29, 117-118; Harrold, Subversives, 140-141.

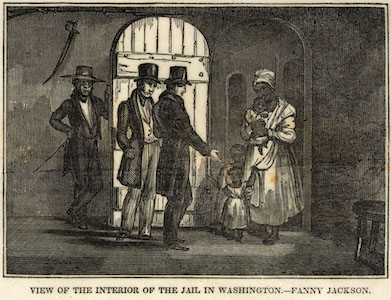

Both Reuben Crandall and the men who aided the fugitives on the Pearl, Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres, were confined in the City Jail. Located in Judiciary Square, the building that housed the jail changed between 1835 and 1848. The jail that held Crandall during his trial was the city's first jail, built in 1802. A two-story building, the lower floor was organized into sixteen eight feet square prison cells, while the upper floor housed debtor apartments. After a few decades, the conditions were notoriously poor. It was overcrowded, unsanitary, and its prisoners uncared for. According to one 1826 report before Congress, city physicians who had visited the jail "pronounced it, in the strongest terms, unfit for the habitation of human beings."1

On one visit, a congressman from Pennsylvania described encountering enslaved petitioners who were awaiting trial for their freedom:

In one of these cells were confined at that time seven persons—three women and four children. The children were confined under a strange system of law in this District, by which a colored person, who alleges he is free, and appeals to the tribunals of the country, to have the matter tried, is committed to prison till the decision takes place. They were almost naked; one of them was sick, lying on the damp brick floor, without bed, pillow, or covering. In this abominable cell these seven human beings were confined, day by day, and night after night, without a bed, chair, or stool, or any other of the most common necessaries of life; compelled to sleep on the damp floor, without any covering but a few dirty blankets.2

In 1838, construction on a new jail in Judicial Square began, and by 1842, the new building was in use. Daniel Drayton described it in detail in his 1855 memoir:

The Washington prison is a large three-story stone building, the front part of the lower story of which is occupied by the guard-room, or jail-office, and by the kitchen and sleeping apartments for the keepers. The back part, shut off from the front by strong grated doors, has a winding stone staircase, ascending in the middle, on each side of which, on each of the three stories, are passage-ways, also shut off from the stair-case, by grated iron doors. The back wall of the jail forms one side of these passages, which are lighted by grated windows. On the other side are the cells, also with grated iron doors, and receiving their light and air entirely from the passages. The passages themselves have no ventilation except through the doors and windows, which answer that purpose very imperfectly. The front second story, over the guard-room, contains the cells for the female prisoners. The front third story is the debtors' apartment.3

The men, women, and children from the Pearl were kept in the jail after their capture, but for some, their imprisonment was short-lived. As Drayton remembered, "the unfortunate people who had attempted to escape in the Pearl had to pay the penalty of their love of freedom. A large number of them, as they were taken out of jail by the persons who claimed to be their owners, were handed over to the slave-traders."4 Most of the slaveholders sold the Pearl escapees to slave traders in Baltimore as both a punishment and a warning to any enslaved person who might consider an escape attempt.

1. Francis Regis Noel and Margaret Brent Downing, The Court-house of the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Judd & Detweiler, Inc., 1919), 90; Annals of Congress, March 1, 1826, 1479-1481.

2. Annals of Congress, March 1, 1826, 1480-1481.

3. Daniel Drayton, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton (Boston: Bela Marsh, 1853), 43-44.

In 1848, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Depot was located on Pennsylvania Avenue near the Capitol Building. The ticket office was a former boarding house that had been modified into a depot building. The Washington Branch of the B&O ran between Washington and Baltimore beginning in August 1835, carrying both freight and passengers the forty mile trip in around two hours.1

John I. Slingerland, a congressman from New York, was present at the depot when many of the fugitives from the Pearl were gathered for sale by slave dealer, Hope H. Slatter. The Albany Evening Journal published his account, which was reprinted in newspapers around the country.

Last evening, in passing the Rail Road Depot, I saw quite a large number of colored persons gathered round one of the Cars, and from manifestations of grief among some of them, I was induced to draw near and ascertain the cause.—I found in the car toward which they were so eagerly gazing, fifty colored persons, some of whom were nearly as white as myself. A large majority of the number were those who attempted to gain their liberty last week in the schooner Pearl.—About half of them were females, a few of whom had but a slight tinge of African blood in their veins;—they were finely formed and beautiful.—The men were ironed together, and the whole group looked sad and dejected. At each end of the car stood a ruffian-looking guard, with large canes in their hands. In the middle of the car stood the notorious slave dealer of Baltimore, who is a member of the Methodist Church, in good and regular standing. He had purchased the men and women around him, and was taking his departure for Georgia. . . . Some of the colored people outside, as well as in the car, were weeping most bitterly. I learned that many families were separated. Wives were there to take leave of their Husbands, and Husbands of their Wives; Children of their Parents, and Parents of their Children.—Friends parting with Friends, and the tenderest ties of Humanity severed at a single bid of the inhuman Slave Broker before them. A Husband, in the meridian of life, begged to see the partner of his bosom. He protested that she was free—that she had free papers, and was torn away from him, and shut up in jail. He clambered up to one of the windows of the car to see his Wife, and, as she was reaching forward her hand to him, the black-hearted Slave Dealer ordered him down. He did not obey. The Husband and Wife, with tears streaming down their cheeks, besought him to let them speak to each other. But no; he was knocked down from the car, and ordered away! The bystanders could hardly restrain themselves from laying violent hands upon the brute.2

A later article identified the Bells as "the family that were referred to with so much effect by Mr. Slingerland, the representative from our Albany district, and the time of the flagitious transaction last Spring."3

1. Washington Topham, "First Railroad into Washington and Its Three Depots," Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 27 (1925): 175-247.

2. Albany Evening Journal, April 26, 1848; "The Recaptured Fugitives," The North Star, May 12, 1848.

3. "Beauties of the Slave System," The North Star, October 13, 1848.

Many of the freedom seekers from the Pearl were purchased from their enslavers by Baltimore slave dealer Hope H. Slatter. Slatter seems to have arrived in Baltimore around 1837 and began dealing in the interstate slave trade later that year. He boasted "a large and extensive establishment and private jail, for the keeping of slaves . . . the building having been erected under his own inspection, without regard to price; planned and arranged upon the most approved principle, with an eye to comfort and convenience, not surpassed by any establishment of the kind in the United States. . . . I also will receive, ship, or forward to any place, at the request of the owner, and give it my personal attention. . . . I am always purchasing for the New Orleans market."1

All of the Pearl freedom seekers were likely headed for the New Orleans market including the Bells. Their youngest daughter, Eleanora, remained enslaved by Susan Armstead, while Mary, seven of her children, and two grandchildren were to be sold. Thomas Blagden, the lumber merchant who had aided Daniel in his freedom arrangement with the colonel, was able to supply $400 to purchase Mary and one of the children. According to one newspaper account, "with the exception of his wife and two younger children," the rest of Daniel's family "were all sold and scattered over the South." It is possible that this number includes Eleanora, who was enslaved but still remained in D.C., or perhaps Daniel had enough money to also purchase the freedom of his second youngest daughter, Harriet.2

Daniel Bell's 1877 will and later probate records reveal the extent to which this final sale decimated the family. There is no mention of Andrew or George, nor of Caroline's two children, John and Catherine. The eldest daughter, Mary Ellen, had been sold to Mississippi, and her brother Daniel, to Louisiana. But in spite of enslavement, the ties of the Bell family were strong. After the war, Mary Ellen and Daniel were able to send word back home to their parents. Caroline returned to the District, and Mary and Daniel were able to know their grandchildren by Eleanora and Harriet.

Mary outlived her husband by seven years. Though "weak and failing in body and health and having in view the certainty of death," in his will, Daniel was careful to provide for the wellbeing of his family, and most of all, his "well beloved and devoted wife."3

1. American and Commercial Daily Advertiser, February 9, 1837; The Sun, October 27, 1837; R. J. Matchett, Matchett's Baltimore Directory for 1837-8 (Baltimore: Baltimore Director Office, 1837), 287; The Sun, August 4, 1838.

2. "Beauties of the Slave System," The North Star, October 13, 1848.

3. Last Will and Testament of Daniel Bell, December 27, 1875, Washington, D.C., Wills and Probate Records, 1737-1952, Ancestry.com; Kaci Nash, "Emancipating the Bell Family: An Inquiry into the Strategies of Freedom-Making," O Say Can You See, https://earlywashingtondc.org/stories/emancipating_bells.

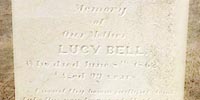

Lucy Bell lived to see slavery abolished in the nation's capital. The Compensated Emancipation Act, which became law in April 1862, freed her granddaughter, Eleanora, and her great-granddaughter, Caroline. But the fate of the rest of her family held in slavery had yet to be decided. She died on June 8, 1862, at the age of 99. Her children commissioned a prominent headstone and laid her body to rest in a burial plot in Congressional Cemetery. Ann was buried alongside her a decade later.1

Her headstone reads:

In

Memory

of

Our Mother

Lucy Bell

Who died June 8th 1862

Aged 99 years.

Unvail thy bosom faithful tomb

Take this new treasure to thy trust

And give these sacred relics room

To slumber in the silent dust

1. "Petition of Sarah Jane O'Brien," May 5, 1862, in Civil War Washington, citing Records of the Board of Commissioners for the Emancipation of Slaves in the District of Columbia, 1861-1863, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 217.6.5, https://civilwardc.org/texts/petitions/cww.00013.html; Gravestone of Lucy Bell, Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C., Range 24, Site 113.

Researched and written by Kaci Nash; edited by William G. Thomas III.

Principal Primary Sources

James Ash v. William H. Williams. In O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, edited by William G. Thomas III, et al. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. https://earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.caseid.0149

Ann Bell, Daniel Bell, & David Bell v. Gerard T. Greenfield. https://earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.caseid.0104

Daniel Bell v. John Stephenson. https://earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.caseid.0117

Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead. https://earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.caseid.0174

Joe Thompson, Nelly Thompson, & Sarah Anne Thompson v. Walter Clarke. https://earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.caseid.0036

The North Star, May 12, 1848, and October 13, 1848.

District Of Columbia, Memorial of inhabitants of the District of Columbia, praying for the gradual abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia (Washington: Printed by Gales & Seaton, 1828), https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.supp.0004.001.

Harriet Beecher Stowe. The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin. Boston: John P. Jewett and Company, 1854, 310-311, 334-335.

Michael Shiner, The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, ed. John G. Sharp, Naval History and Heritage Command, Introduction, 52, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html.

Francis Scott Key, A Part of a Speech Pronounced by Francis S. Key, Esq. on the Trial of Reuben Crandall, M.D. (Washington: 1836), YA Pamphlet Collection (Library of Congress), 9-12, https://www.loc.gov/item/31010419/.

The Trial of Reuben Crandall, M.D. (New York: H. R. Piercy, 1836), https://www.loc.gov/item/18013204/.

The Trial of Reuben Crandall, M.D. (Washington: 1836), https://www.loc.gov/item/18013203/.